The adoption of digital technologies has accelerated dramatically during the pandemic. Now patients want more influence on how technologies are designed and how their data is handled

The digital tools needed to support remote consultations and to monitor key health indicators have been around for a while. Sometimes it takes a shock to jolt health systems into radical change. The pandemic provided a sudden shift in people’s willingness to try new things in the interest of patient safety and protecting continuity of care. Some are calling it a moment of tech-celeration.

‘We saw 10 years’ change in just a few months,’ says Prof Martin Cowie, Professor of Cardiology, King’s College London, and Chair of the ESC Digital Health Committee. ‘It can be challenging to have a conversation with someone you’ve never met, but for many interactions, online consultations are a convenient way for patients and doctors to catch up.’

Speaking at the Global Health Hub UNITE Summit, he said that as services adapt to new ways of working, patients and clinicians should collaborate to find the right blend of tools to be used at different points of the patient pathway. ‘I hope to see more co-design with patients,’ he said. ‘Let’s not fear the future: we need to hold on to the creativity and innovation that COVID-19 forced us to embrace.’

Accelerating patient empowerment

The impact on the clinician-patient relationship could be long-lasting, according to several experts who noted that the pandemic catalysed an existing trend towards patient empowerment. Dr Petra Wilson, CEO, Health Connect Partners, said shifting the location of care changes the dynamic in ways that favour better patient experiences. ‘Care is no longer on the healthcare provider’s turf,’ she said. ‘There are also opportunities to collect Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) alongside clinical data so that we have a more personalised approach to care.’

However, Dr Wilson was quick to note that there are several challenges to realising this ideal scenario, including challenges accessing technologies, interoperability issues, limited human resources, and lack of reimbursement. ‘We need to be careful that as we move forward, we don’t leave people behind.’

This was echoed by Dr Jean-Luc Eiselé, CEO, World Heart Federation, who noted that access to high-speed broadband and digital devices, as well as health and technological literacy, are low in many parts of the world. In addition, he expressed concerns about the collection and use of data: patients often have limited visibility of their health information and are not necessarily in control of how it is used.

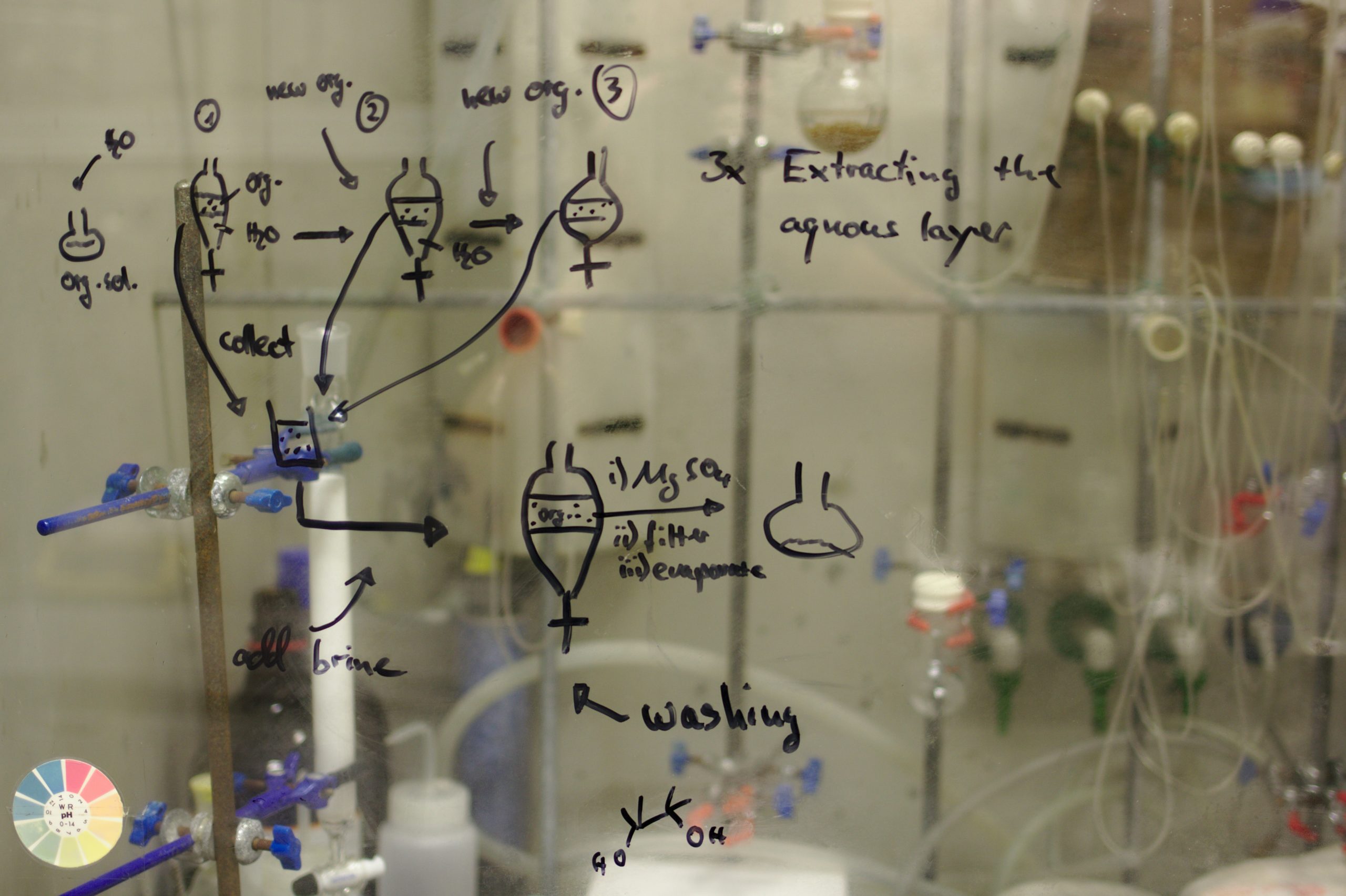

Despite this, Dr Eiselé highlighted opportunities for transition in cardiovascular care. ‘A lot of monitoring is performed using non-invasive technologies – unlike in gastroenterology, for example,’ he explained. ‘Patients can generate data at home and share it with healthcare providers. This will require an element of mutual trust but presents a real change to promote prevention.’

Equality of access remains a key barrier to ensuring the benefits of innovation are universally shared, according to Dr Ratna Devi, Chair, International Alliance of Patient Organisations; CEO and Co-founder of DakshamA Health and Education. ‘Global apps are often in English which can be hard for some populations to use, and very senior or very young people cannot use these apps,’ she said.

Data access and portability should also be addressed, Dr Devi added. ‘Patients with multiple conditions may see several specialists, each using different apps that don’t talk to each other,’ she said. ‘And we know that healthcare providers are often reluctant to provide patients with a full picture of their electronic health records – even though they may be entitled to it.’

While solutions to these issues will not come easy, the best shot at building a more personal and patient-focused future comes from dialogue between stakeholders. This takes time and resources to collaborate on future innovation priorities and even on product design.

‘Co-creation is the answer,’ said Dr Wilson. ‘But it doesn’t come for nothing. Patient representatives will need to lobby hard to get the funding needed to engage in this work. Without broad patient representation, we’ll end up with algorithms biased in favour of those with the resources to shape future technologies.’