Patient representatives and researchers are working with PFMD on a forthcoming guide to involving patients in clinical trials. We speak to two patient advocates about how collaboration can make studies more appealing to patients and reduce drop-out rates

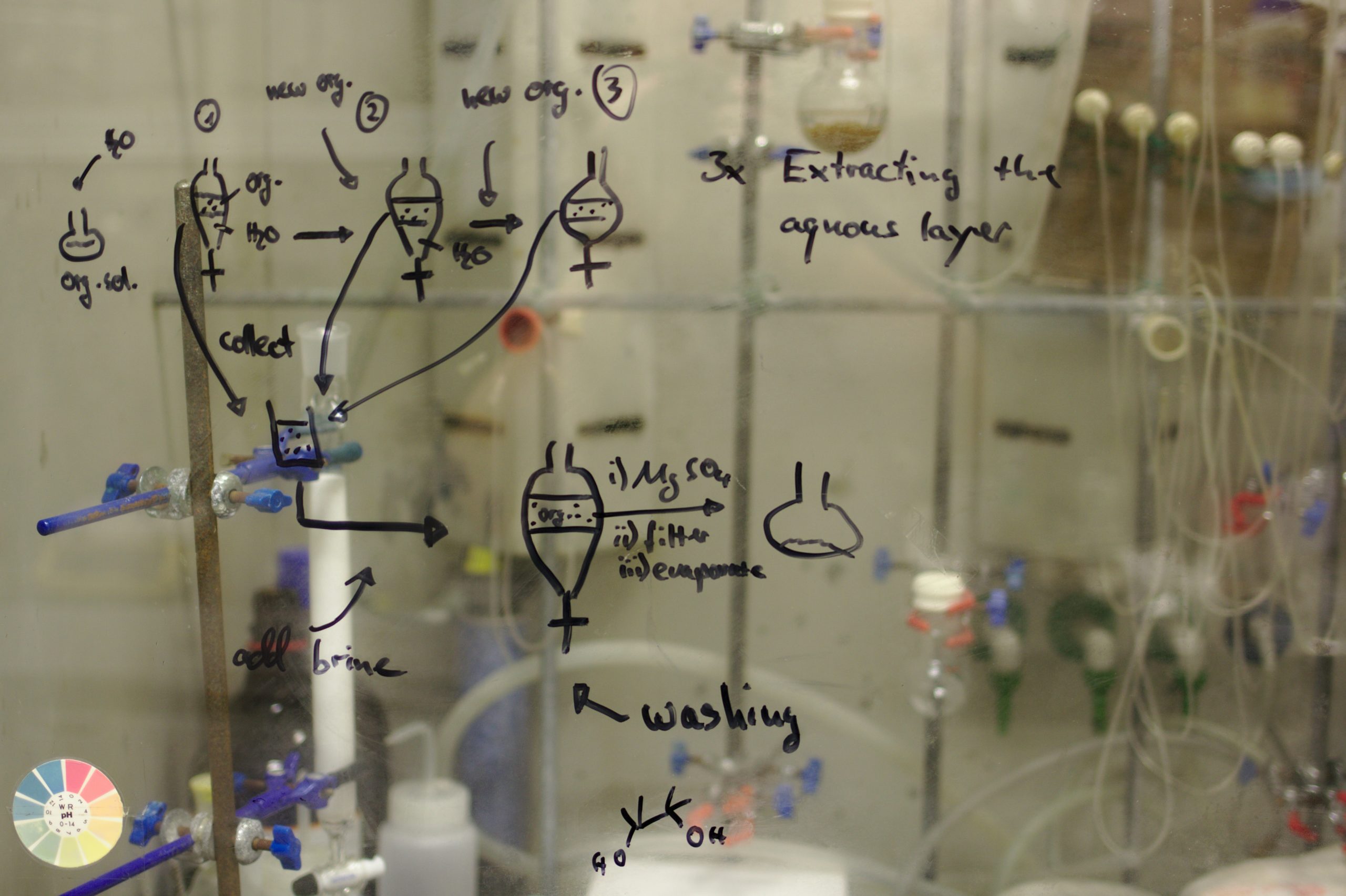

Clinical research can be time-consuming and costly for scientists and sponsors, and maybe a burden on those participating. One way to make patient recruitment easier, and to reduce the number of people who drop out of trials before their conclusion, is to involve patients in designing studies.

‘If patients are involved in the design and execution of trials, it makes the studies more patient-friendly and more responsive to the needs of patients,’ explains Rob Camp of Eurordis. ‘And if the results of the trial are positive, they will be more easily implementable in the patient population.’

While this simple idea has been gaining momentum in recent years, making it happen can be daunting. That’s where the PFMD How-To Module on Clinical Trials will come in. The module will form part of a suite of guidance documents that offer tools for implementing patient engagement at each stage of the drug development lifecycle.

Created by multidisciplinary groups, including patients, industry and academics, the aim of the modules is to provide practical help to those who are keen to make patient engagement the norm. Rob, who is contributing to Working Group 2b, says this approach could deliver better quality trial data than the traditional silo approach to trial design.

‘In the past, clinical studies were designed and devised by research professionals who may have had little or no contact with the patients they hope to recruit,’ he says. ‘Research often gave too little weight to practical and quality of life issues that protocols might have for patients – including the time of administering treatment, frequency of clinic visits and blood sampling.’

As a result, committing to trials can be unappealing to some patients, while the real-world burden of staying in a trial for months leads some to drop out early. ‘We hope that collaboration will make recruitment faster and that retention will be better,’ says Rob. ‘This gives more robust data for analysis and may give a more accurate picture of how the intervention will fare in a real-world setting.’

Involving patients in How-To modules

The How-To module will address all stakeholders in clinical research and benefits from strong involvement from patients in writing the guide. ‘Patients are genuine partners in the working group,’ says Duane Sunwold of the National Kidney Foundation. ‘It has been fascinating to work with this international group. We share a passion for making patients partners in research and face many of the same challenges regardless of our location.’

Duane, a chef and college instructor, has been a vocal patient advocate since contracting a rare kidney disorder at the age of 40. His experience combining medication with radical dietary changes had helped to improve his quality of life – and his health. Along the way, he has seen a greater willingness to embrace patient engagement as well as gaps in education for research stakeholders on how to work together.

‘If you want patients to be involved in clinical research, you have to spend some time educating them so that they are comfortable walking into a room full of clinicians,’ he says. ‘It’s also important to work with clinicians so that they appreciate the benefits to their field and can communicate effectively with patients and carers.’

Duane says patients are helping to make research more efficient by writing or editing survey questions, and by communicating the burden of adding additional medications to a patient’s drug regimen.

‘Clinicians think they know the life of a patient but since they don’t walk in the patient’s shoes, they miss some key elements,’ he explains. ‘For example, if a patient’s identity is linked to their condition, adding a medication may make them feel like their disease – and their identity – is deteriorating. Plus, medication can come with side effects so patient input is essential when deciding on dosage, frequency and the acceptability of side effects.’

The working group, which includes 14 core team members and 10 reviewers, aims to publish its work at the end of 2020.