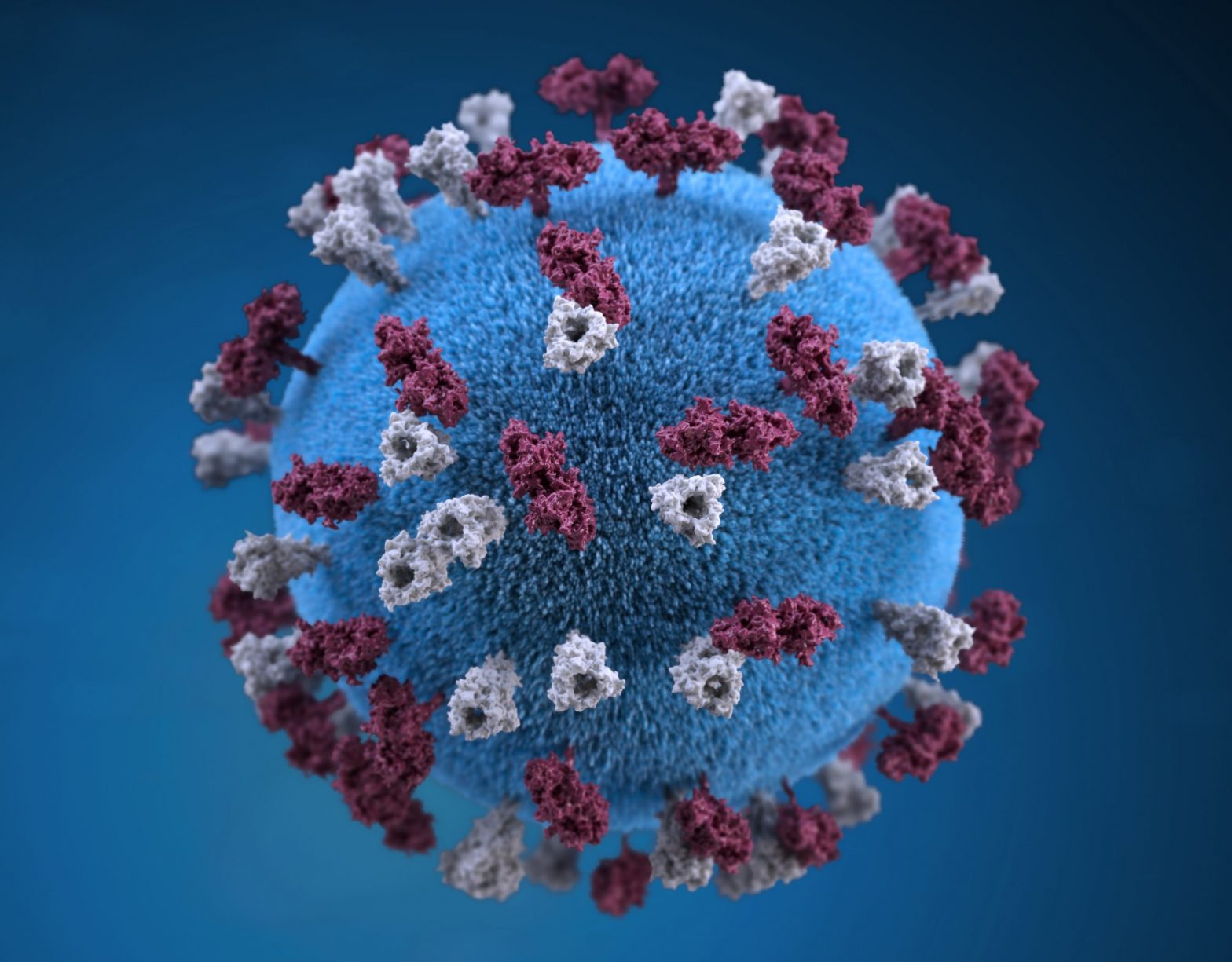

Researchers and ethicists are usually hesitant to deliberately expose volunteers to a virus, but thousands of people have signed up to help fast-track clinical trials

The world needs a vaccine against coronavirus. However, vaccine development can take more than a decade. But with politicians demanding a vaccine be developed at ‘warp speed’, many people are growing impatient. Some are looking for ways they can help inject new urgency into a painstaking process.

Almost 30,000 people in 102 countries have signed up for a ‘challenge trial’ in which volunteers are deliberately exposed to a virus to test whether an experimental vaccine protects them. The One Day Sooner project – which is not linked to any university, hospital or company – says accelerating vaccine development could save millions of lives and allow the world to return to normal.

Human challenge trials have been the subject of intense ethical debate for decades. Put simply, these studies deliberately put lives at risk in the hope of answering research questions more quickly – a fact that must be thoroughly explained to volunteers.

Prior to the coronavirus pandemic, the WHO published a paper outlining the difficulties associated with challenge studies but left the door open to their use in exceptional circumstances where the highest level of precautions can be taken. One of these hypothetical scenarios was ‘an influenza pandemic’.

Today, faced with a respiratory virus that spreads more quickly than influenza and appears to have a higher death rate, the WHO has softened its stance – while maintaining strict conditions under which challenges studies can be considered.

Josh Morrison, the founder of One Day Sooner, says the risks associated with accelerated vaccine development are worthwhile. He compares the ‘sacrifice’ of volunteering for challenge trials to the risks taken by emergency health workers to support community health.

Why are vaccine trials so slow?

To understand why human challenge trials are back on the table, we need to look at how vaccines are developed in normal times. Like all clinical trials, vaccine development takes time, money and volunteers willing to be among the first people to receive a new medicinal product.

But there are key differences between trials for vaccines and trials for medicines. For a start, while new cancer therapies are typically trialled in patients with the disease, potential vaccines are given to healthy people even in late-stage clinical studies. Healthy people have a lower tolerance of side effects: with a cancer drug, for example, patients might accept some unpleasant effects if it extends their lives or improves the quality of life in other ways. Healthy people receiving vaccines generally accept the risk of short-term pain in the arm, but that is usually as far as it goes.

The biggest difference between medicines and vaccines trials is measuring end-points to determine whether the product works: doctors can assess whether cancer patients feel better; they can check biomarkers in the blood and look at MRI or CT scans.

With vaccines, researchers are looking for the absence of disease. But, to draw conclusions about the efficacy of a vaccine, they need evidence that the volunteer was exposed to the pathogen (a virus or bacteria) that they hoped to protect against. The usual approach is to give one group of patients the new vaccine and give another group an existing vaccine (for example against meningitis or flu) and follow them for a long time – often years.

Therein lies the problem. As short-term lockdowns and ongoing social distancing measures dramatically reduced the amount of coronavirus circulating in our communities, the risk of catching the virus ‘in the wild’ has fallen. It would take years before researchers know whether their candidate vaccine works. In the unique context of a global pandemic, the world doesn’t have time to wait years for a vaccine.

Ethical trial design

Renowned medical ethics expert, Dr Arthur Caplan of the New York University Langone Medical Center, says the current crisis justifies the use of human challenge trials. However, he believes these should be strictly controlled and volunteers must give informed consent. They should also have access to the best possible care and must be quarantined from the wider community to prevent sparking fresh outbreaks.

‘I favour doing them [challenge trials]. It’s important that participants are observed closely and are near a hospital where they could receive the best possible care if needed,’ he says. ‘This can be justified if they are volunteers who are competent and understand the risks.’

Even well-designed trials bring new dilemmas. For example, to minimise the risks to volunteers, healthy people will be recruited. But the first in line for any approved vaccine would be high-risk individuals.

‘You would take younger people with a lower risk of consequences,’ says Dr Caplan. ‘If a vaccine is safe and effective, it might become morally justifiable to include higher risk groups, such as older people.’

Challenges ahead

Despite the risks involved in challenge trials, it seems certain that several research groups will take this route to vaccine development this year. UK and US companies have already indicated that they hope this approach will accelerate the development process, while Belgium has invested €20 million in a state-of-the art facility in Antwerp that could be contracted by companies with vaccine candidates.

While there is much uncertainty about what happens next, we can be sure that when the history of the 2020 coronavirus pandemic is written, the chapter on vaccine development will focus on the role of altruistic healthy volunteers. Whether this is a success story, remains to be seen.