How can real-world data be captured and shared in ways that marry the needs of patients and researchers?

Patients’ lived experience is increasingly viewed as a valuable datapoint in understanding and addressing unmet health needs. Research suggests patients will share information about their health, providing they trust those who collect and use it, but security and privacy concerns persist.

The task of building responsible models for sharing data has been a recurring theme of the 2021 Patient Engagement Open Forum series, co-organized by PFMD, the European Patients Forum and EUPATI. An April webinar explored ways that patients could become central to the health data landscape, while a June session looked at the guiding principles that should underpin this rapidly evolving field. Patients, industry representatives, clinicians and other experts joined an interactive PEOF meeting on 7 December to expand on this work.

Veronica Popa, Digital Patient Engagement Manager at EURORDIS, Rare Diseases Europe, said patients need to play a bigger role in shaping the decisions that affect them. This increasingly includes the use of health data in research and care. The key to achieving a suitable framework for data sharing is to use existing tools in a way that reflects the needs of stakeholders. ‘We have the ingredients to ensure data is shared in a responsible way,’ Ms Popa said. ‘Rather than a revolution, the goal should be to find the right balance.’

The Rare Barometer, a survey of patients with rare diseases, found that 97% of respondents would share their information to help advance medical research, but there was much less support for providing data that would be used for non-medical purposes. Patients want control over their data, according to the study, and place varying degrees of trust in different stakeholders. Doctors and patient organizations were significantly more trusted than government, private researchers and insurance companies. ‘Transparency and accountability are essential to that trust,’ she said. ‘People want to know who will use the data and how; they want to know the impact their data has and that the risk they took in sharing information was worthwhile.’

Stories + Science = Success

Sarah Krug, CEO, of the Health Collaboratory and Executive Director at Cancer101, described patient stories as the ‘oldest diagnostic tool’ in medicine. ‘Understanding the personal and societal challenges a person faces is essential to understanding their expectations and helping them get better.’

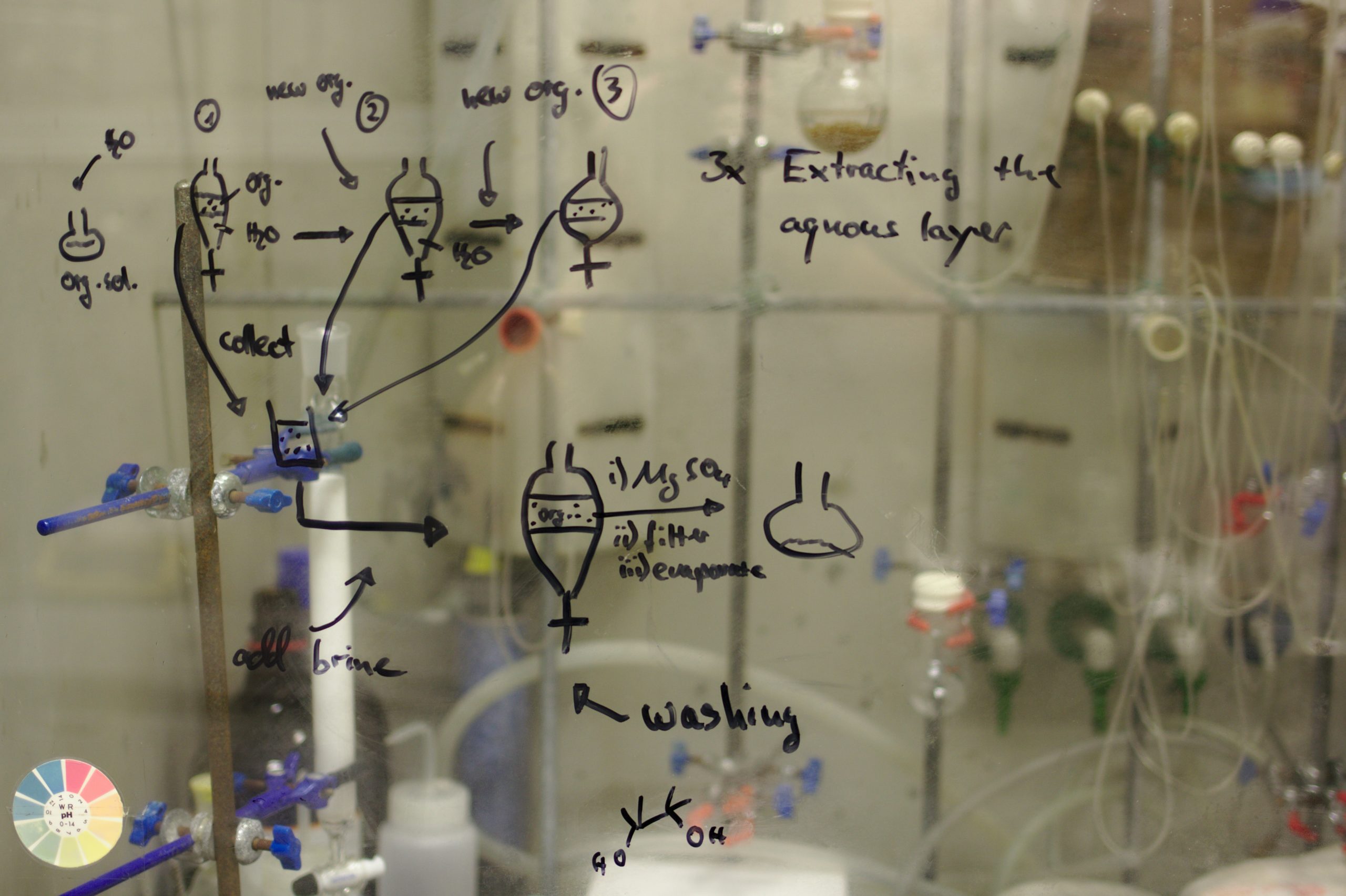

Translating patient stories into science is challenging but can help to develop actionable data. Krug’s organization is working with clinicians, hospitals and companies to capture patient experiences using a variety of tools. For example, the Life Impact Tool tracks how a patient’s condition is impacting 10 key aspects of their life, including personal relationships, mental health and financial wellbeing. A new tool, HealthUntangled, will launch in 2022 aiming to simplify the wealth of data generated by patients.

One of the challenges in capturing health data from social media influencers, advocacy groups or from outspoken patients posting on discussion forums, is that it risks leaving some people behind. ‘The data could be biased towards those who actively share their information, missing the diverse patient community who are often less visible,’ she said. The Health Collaboratory’s Patient Shark Tank seeks to address this by engaging patients virtually and anonymously.

‘Data stream’ vs database

The need to establish long-term relationships between patients and researchers was highlighted by Sharon Terry, President & CEO of Genetic Alliance, and Dawn Barry, President & Co-Founder of Luna PBC. The two organizations collaborate to collect information on real-world experiences and to ensure patients and researchers can stay connected in ways that respect privacy laws. ‘The patient community has information on self-reported, long-term lived experiences of patients,’ Ms Terry said. ‘Industry wants longitudinal, real-world data that is representative of patient experiences so that they can improve outcomes. Our approach lifts both sides.’

Ms Barry shared a case study showing how a leading biopharma company used this approach to gain insights into KCNT1 epilepsy, a rare condition for which there was no patient advocacy group at the time of the study. More than 200 parents of 115 children were recruited globally, creating a critical mass of individuals who could shape patient-centered drug development. Together, they built an ongoing relationship focused on seizure reduction as well as sharing ideas on ways to address symptoms such as constipation.

While privacy and data protection rules are often seen as a hurdle to this kind of work, Ms Barry said the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) ‒ often viewed as the strictest in the world ‒ is ‘a beacon’ for international standards on data management. ‘We default to the most stringent standard,’ she said. ‘We bear the burden of the data controller role while giving patients control of their data, an understanding of what it is used for, and the right to be deleted.’

Ms Terry said this new way of working is faster and more representative than Delphi surveys and focus groups. It uses methodologies that have been deployed by innovative companies such as Microsoft, Google and Apple to accelerate innovation and discovery, and applies them to community-driven health research.

The meeting included a co-creation session that allowed participants to propose and rank success factors for creating the patient-centered health data models of the future. This work will be taken forward by PFMD, EPF and EUPATI as part of their work on patient information.