An innovative funding agency in Austria is crowdsourcing opinions to set research priorities – and engaging patients at every step of the scientific process

Patients are playing an increasingly active role in scientific and medical research. From designing clinical trials to raising awareness of new technologies, the patient voice is helping to shape how research is conducted.

The Ludwig Boltzmann Gesellschaft (LBG) – a research funding body in Austria – is going one better. Through their Open Innovation in Science Center, the LBG is crowdsourcing public opinion on where to direct its funds.

‘We are trying to open up research processes and include patients every step of the way,’ explains Dr Benjamin Missbach, Project Manager at LBG. ‘Crowdsourcing research questions is like research priority setting on a grand scale. Patients tell us what are the most pressing issues for them, and we identify projects that are worth putting money into.’

The crowdsourcing exercise – called Tell Us – transforms patient priorities into research outputs. One of the first crowdsourcing exercises was on mental health; this led the research groups to focus on how children are affected by growing up with parents who are living with a mental illness. (Read more here and here)

Joining the dots

The growing Open Innovation in Science team, established in 2016, is developing a framework for its 21 research institutes, helping them to apply open methods in their work. ‘We have screened the literature to see what’s out there in the open innovation space,’ explains Dr Missbach. ‘This is part of our work with research institutes and open innovation champions to co-create a framework to guide future activity in this area.’

The framework will be built through a Patient and Public Involvement & Engagement (PPIE) project that will support researchers and address challenges to greater uptake of open innovation models. To help drive this initiative forward, the team recruited Roi Shternin – a patient, health entrepreneur and start-up founder. He brings a patient perspective as well as experience developing healthcare apps.

Shternin diagnosed himself with a rare condition (POTS Syndrome) after years of suffering without medical treatment, setting him on a path to improve healthcare. This was a catalyst to his work in digital medical devices and health education.

‘My task is to connect the dots between healthcare, patients and research,’ he says. ‘My experiences as a patient who underwent therapy and participated in joint research projects with a leading hospital in Israel, as well as experience as a founder, brings a unique perspective that is something missing in research institutes.’

Incentivising engagement

Finding the right mix of incentives for researchers and patients is essential to accelerating uptake of open innovation methods. The team is currently training researchers, exploring ways to make collaboration easier, and highlighting successful examples of how it is done.

Busy academics sometimes worry that an open approach would become time-consuming and cumbersome, so the Open Innovation in Science Center wants to help by connecting them with patient groups and developing easy-to-use tools for co-creation. It is also offering access to a training programme called Lab for Open Innovation in Science.

Patients too need incentives. Shternin’s experience as a founder of a patient organisation in Israel helped him to appreciate that patients are keen to collaborate, but they sometimes need training, support and monetary incentives if they are to commit their time.

Rethinking research

The Open Innovation in Science team already has several examples of how to engage the public in research projects, and encourages open innovation ‘champions’ to become representatives in academic circles.

The team is working with the Institute of Applied Diagnostics on a prostate cancer project. Survival rates for prostate cancer are very high, especially if treatment is offered early. This means there is a large cohort of people living long-term with the disease.

‘We are building a technology – essentially a bot – that will gather information about the experience of chronic prostate cancer patients and help to direct future research funding decisions,’ he says.

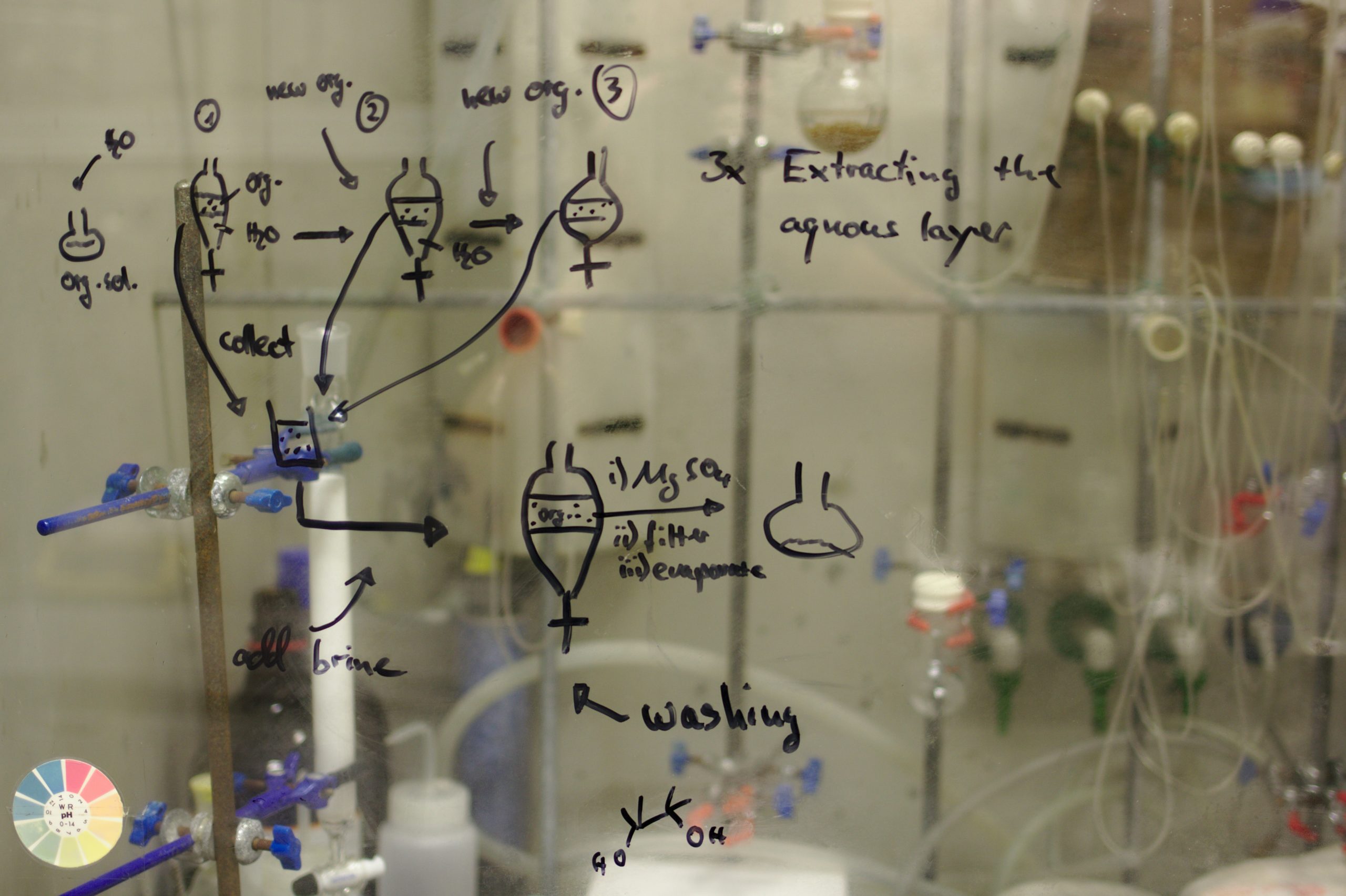

The technology was developed using a hackathon that brought together 20 medical students, professors, and others, to come up with a way to encourage patients to share their experience while offering something in return. The team spoke to patients throughout the hackathon to ensure they were on the right track and that patients would engage with the proposed technology.

The resulting ‘bot’ could sit in a companion app that provides patients with information about their condition and other ways to improve their quality of life. It could also potentially be built into patient information websites, providing access to an existing community of motivated patients. When it goes live, it could become an efficient way to collect a large dataset of patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) on a group sometimes considered ‘hard to reach’.

‘For us, this was an attractive project because we are dealing with older patients in a disease area that can be sensitive or stigmatised,’ says Dr Missbach. ‘We think that if we can crack this, we can show that it’s possible to work with any patient group.’The young team, which will recruit its 20th member this year, is taking LBG on a journey that will transform it into a more responsive and collaborative organisation. As it forges ahead, other funding agencies will watch with interest to see whether it can successfuly reinvent the research funding model.